Now that we’ve covered the changes to the Alcohol Duty System that are coming in later this year, in August, it’s worth looking at how this will affect the industry as a whole.

We’ve seen from the cider article that cider producers are now able to creep over their previous 7,000 litre farmgate allowance, with those making lower strength ciders able to produce an additional 4,000 litres, and those making higher strength cider able to produce another 128 litres before paying any duty. And when they do grow above the new threshold the amount of duty they’ll be liable for is a lot less than previously, paying £1.59 per litre of pure alcohol compared to £5.55 before.

And it’s even better for those making Made Wines (cider with fruit in) as previously they weren’t able to get any duty relief, but now are able to claim as though it were cider.

But to see how this new system is going to affect the beer industry we need to look back at why this all came about in the first place. That’s right, the Small Brewers Duty Reform Coalition (SBDRC), a group of medium to large brewers backed by multi-nationals who employed a consulting agency to use outdated economies of scale figures to try and get a tax break on their beers at the expense of the smaller breweries they saw as competition. And it looks like they’ve got it in through the back door.

One of the major changes to the Alcohol Duty System is that the amount of relief a brewery gets is now based on the amount of pure alcohol they made the previous year. It used to be that the amount of duty liable was based on the level of alcohol in the beer and the relief was based on overall beer production volumes the previous year. The larger the brewery, the less relief.

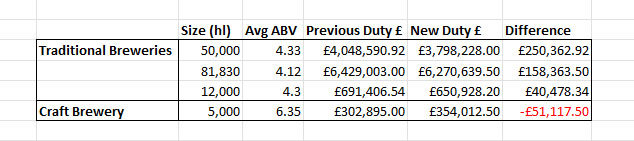

So a brewery producing up to 5,000hl of beer would get 50% duty relief whilst a brewery producing 12,000hl would get 24.7% relief, a brewery producing 50,000hl would get 1.9% relief, and a brewery at 81,830hl wouldn’t get any relief at all as the relief only went up to 60,000hl of beer production.

These figures may seem strange ones to pick, but 5,000hl of beer per year was the most that a brewery could produce and still get the full 50% duty relief. The other three are the production volumes of breweries who were members of the SBDRC.

One of the main arguments for the change to the duty system was the “cliff edge” that prevented breweries from growing past the 5,000hl level. The amount of relief after this level plummeted quickly, making it economically unviable for a brewery to grow beyond it unless they grew quite a lot, which in itself was a large financial risk.

But with the amount of duty relief a brewery receives now being based on the volume of pure alcohol produced rather than the volume of beer, we’re seeing what I would like to hope is an unintended consequence, although the cynic in me refuses to believe that.

A brewery can now produce 9,000hl of beer at an average of 4% abv, or 6,000hl at an average of 6% abv, and they would both be liable for the same duty relief.

That’s right, a brewery half the size again will get the same tax break as the smaller one because it produces lower strength beers.

This is highlighted quite brutally when we look at the production volumes and savings likely to come to members of the SBDRC who all brew lower strength traditional ales, compared to a modern craft brewery who does a range of DIPAs and TIPAs of higher strength.

The average abvs used here are extrapolated from the beers that these breweries produce and the likely quantities of each given the overall production volumes at the time SBDRC were calling for a change in the duty system. If any of those breweries would like to provide me with more accurate volumes I’ll happily amend this accordingly.

The “sweet spot” of the new system falls at an average of 4.5% abv. If a brewery produces beers with an average above that they will be liable for more duty than they currently are.

A lot of the modern craft breweries that have sprung up in the last ten years are producing beers with a higher average abv than 4.5%. The breweries that have a lower average tend to be the older family and traditional breweries – the members of the SBDRC.

The concept of paying duty based on the amount of alcohol in beer has been around for quite a while now. On 1st October 2011 High Strength Beer Duty equivalent to an additional 25% was introduced to encourage brewers to not make as much strong beer, by levying higher duty on all beer of 7.5% and above. A Lower Strength Beer Duty was also introduced on beers of 2.8% and below, equivalent to 50% relief on the standard duty rate, to encourage breweries to produce lower strength beers.

This didn’t really discourage craft breweries from making stronger beers as most produced their TIPAs and Imperial Stouts above the 7.5% threshold anyway and paid the extra duty on the additional abv %; the alcohol content below the threshold was still liable for the Small Brewers Relief. The new system doesn’t allow for that relief at all, and High Strength Beer Duty is liable on every percentage. And if that wasn’t enough to hit the craft breweries harder, all beer at the newly raised threshold of 8.5% and above might not be liable for duty relief, but will count towards the brewery’s production of alcohol, and therefore their overall duty rate. So all those TIPAs that craft breweries can no longer claim any duty relief on will be pushing up the amount of duty they pay on their Session Pales.

Meanwhile, the traditional breweries’ core beers tended to stay in the low to mid-4% range.

But with encouragement from the Temperance Movement-backed health lobbyists the overall amount of alcohol has now been extended to determining the overall amount of relief too. Working out the overall relief based on the amount of alcohol produced compared to the amount of beer sold seems to punish those more modern breweries who cater to a smaller market.

What we’re seeing with this new system is that the larger, more traditional breweries are getting an additional saving on the amount of tax they pay, whilst also enjoying the economies of scale for purchasing their ingredients, and the smaller craft breweries are footing the bill for it.

This is not a system that will encourage the smaller, newer breweries to grow beyond the previous 5,000hl threshold, but rather may well stifle that growth. It will also discourage the innovation we have seen brought in with these stronger craft beers.